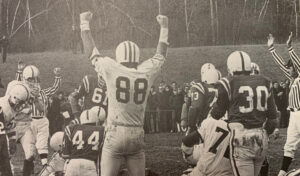

The 1970 Hillers (in white vs. Ashland) compiled a 6-3 record and snapped a seven-game losing streak in the Thanksgiving Day rivalry vs. Ashland. PHOTO/HHS YEARBOOK

Fifty years from now, historians likely will find it fascinating talking to people who lived through the COVID-19 pandemic, which, among other things, forced the postponement of the Hopkinton High School football season and the cancellation of the annual Thanksgiving Day game vs. Ashland. It’s only the second time since the series began in 1923 that no game was played (1940 is the other).

Likewise, it was a pretty interesting time to be a high schooler 50 years ago, with top stories focusing on the Vietnam War, President Richard Nixon and the breakup of the Beatles.

Hopkinton in 1970 was a town with about 6,000 residents, a third of its current population. The Hillers football team faced a stiff challenge on Thanksgiving morning, as Ashland had won the previous seven matchups. It’s a far cry from the way things are now, with Hopkinton having won 17 of the last 19 meetings to take a 53-38-5 lead in the overall series.

The 1970 Hillers were a close-knit group that boasted 24 seniors, according to then-lineman Ed Flannery, who was known to his teammates as Geno. The Hillers posted a 6-3 record that included some impressive wins.

“We had a couple of [memorable] games, like when we played Millis, who came in undefeated at the time,” Flannery recalled. “We just played one heck of a game and we ended up beating them 24-16.”

The 1970 team was the final one coached by the legendary Aubrey Doyle (for whom Hopkinton Middle School’s Doyle Gym is named). Also a math teacher and athletic director, Doyle kept a close watch on his troops. After Friday night film sessions at the high school, Doyle would caution his players to be home by a 9 p.m. curfew.

“He’d say, ‘Just remember, 9 o’clock curfew, I’ll be calling.’ And every now and then he would call your house to see if you were home at 9 o’clock,” Flannery said.

Flannery said the rivalry was taken very seriously — so much so that you had to be careful about paying a visit to the neighboring town in the days leading up to the game.

“Back in that time you didn’t go to Ashland around Thanksgiving, because if some of the Ashland kids saw you it could end up in something that you didn’t really want, like a fight,” he said. “The rivalry was just that big. Same thing with Holliston. You avoided going over there. If they knew you were from Hopkinton you could be in trouble.”

The rivalry occasionally led to acts of vandalism as well, Flannery said, which became evident Thanksgiving morning.

“The game was in Ashland,” Flannery recalled. “We showed up to the high school in Hopkinton so we could get ready. It was cold, and it was foggy that morning. When we looked out onto our field, through the fog, we saw what looked like our goalposts laying on the ground. We took a few steps out there, and sure enough, some Ashland kids had come up the night before and broke off our goalposts.

“It gave our team a little bit more incentive when we went down to Ashland to play that game. There was no way we were going to lose that game, not after that.”

The Hillers also took motivation from the fact that it was going to be Doyle’s final game.

“We knew that Mr. Doyle was going to resign from coaching football at the end of the season,” Flannery said. “We wanted him to go out as a winning coach, and we made sure we made the extra effort to do that. The group of seniors, we also realized that this was the last game we were going to play. We did not want to lose this last game.”

According to The Boston Globe game account, Hopkinton took a 12-0 halftime lead on touchdown runs by Paul Cotter and Terry DeLeo. Ashland recorded its only points on a 1-yard TD run in the third quarter. Hopkinton put the game away in the final period with a 23-yard run by Ricky Phipps, who also caught the two-point conversion pass from DeLeo to cap the scoring. Scott Haynes led the HHS ground game with 80 yards on 20 carries.

Flannery said other contributors on the team included Ted Mayer, Tom Nealon, Tom McIntyre, Ron DiMichele, Eddie Bishop, Paul Beavers, Peter Bowker, Dennis Hayden, Joe Magrini and Gary Garner — some of whom still live in town.

“It was just a great bunch of guys,” Flannery said.

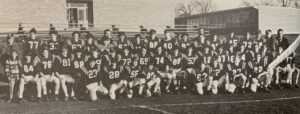

Some of the members of the 1970 Hopkinton High School football team still live in town. PHOTOS/HHS YEARBOOK

Flannery, who went on to serve as an assistant coach for the Hillers for many years until he stepped away after the 2018 season (he also retired as head custodian at Hopkins School last year), said 1970 football looked very different from today’s passing-focused style.

“When we would go out to play we knew it was smash-mouth football, we were going to have to run the ball,” he said. “Almost every team was like that. Nobody really passed back in those days. … Between Mr. Doyle and Mr. [David] Hughes, the theory was, ‘I’m going to beat you down, beat you down, and then I’m going to win the game in the fourth quarter when you’re too tired to stop us.’ That’s the way they would think about it.”

The community also has seen “unbelievable” changes since 1970, Flannery said, notably an influx of developments popping up off the side of previously sparsely populated roads like Ash Street and Saddle Hill Road.

Flannery said there were advantages and disadvantages to being a high school football player in a small town five decades ago.

“A lot of times we would all hang out on Friday night after our movie session with coach, and we might go out and do something stupid, like young boys would. But we all knew each other and liked spending time together,” he said. “But the other thing was if you did something wrong and somebody saw you, they knew who you were. And if you were on the football team, Mr. Doyle might have gotten a phone call. Next thing you know there’s one kid who couldn’t play on Saturday because he wasn’t in before curfew or he did something that brought attention to the football team that was a no-no. He would sit you down. It didn’t matter who you were.”

Added Flannery: “It was a fun time to live in town.”

0 Comments